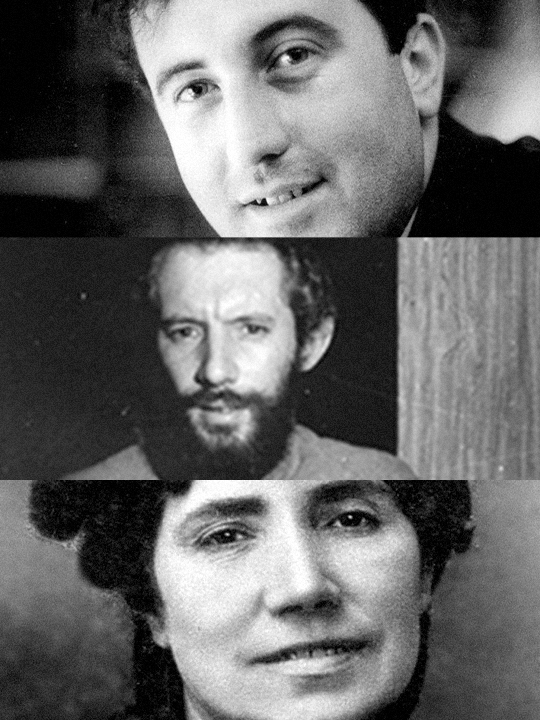

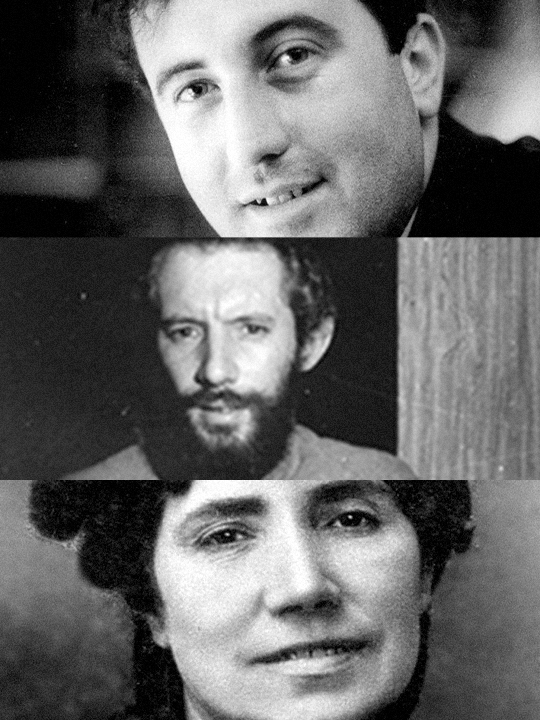

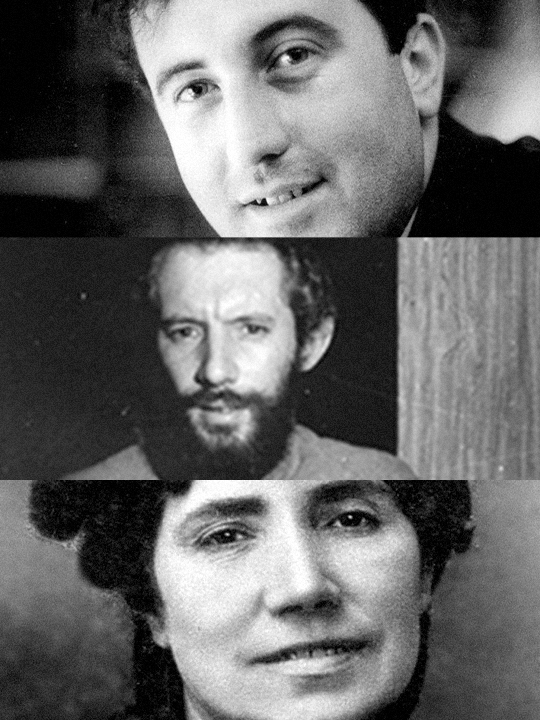

Adriano Correia de Oliveira

+ José Niza + Rosalía de Castro

Adriano Correia de Oliveira + José Niza + Rosalía de Castro

,

Much about the life story of Rosalía de Castro (Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 1837 – Padrón, Spain, 1885) remains hidden by the opacity of her biographical records. A canon of Spanish literature, the poet was responsible for the resurgence of the written Galician language with the publication of her first book, Cantares Gallegos. Between novels and poems, her work is permeated by autobiographical experiences and, at the same time, is set in a social panorama representative of Galicia at the time. The reality of the domestic life of the women of her time, the mass emigration that plagued Galician villages, her clarity of conscience concerning the dominant powers, her deep sense of justice, her fragile health, the loss of two of her children and a tragic sense of life are representative themes in her work — and why Rosalía de Castro is a heroic figure for the Galician people.

José Niza (Lisbon, 1938 – Santarém, 2011) arrived in Coimbra in 1956 to study medicine, the field in which he would eventually train. He was shaped both humanly and politically in a city where the preambles of the revolution soon echoed, above all in the voices of its students. He wrote around 300 songs, including the lyrics to E depois do Adeus, which served as the first signal to the Carnation Revolution on 25 April 1974, performed by Paulo de Carvalho and set to music by José Calvário. José Niza accompanied Ricard Salvat during his time in Coimbra and was invited to compose the music for two shows at CITAC: Bertolt Brecht’s The Exception and the Rule and Ricard Salvat’s Castelao e a sua Época. Correia de Oliveira recorded several songs by José Niza, including Cantar de Emigração, on the album Cantaremos (Orfeu, 1970).

A musician and performer who was part of the history of cultural resistance to Salazar’s dictatorship, Adriano Correia de Oliveira (Porto, Portugal, 1942 - Avintes, Portugal, 1982) actively contributed to the consolidation of the democratic process in Portugal. A member of the Portuguese Communist Party in the 1960s, he took part in the 1962 academic strikes against Salazarism when he was still a law student at the University of Coimbra. The following year, he released his first EP, Trova do vento que passa, a poem by Manuel Alegre, which, in the voice of Adriano Correia de Oliveira, became the anthem of the student resistance to the dictatorship. The anti-fascist struggle and the struggle against the colonial war are inseparable parts of his biography and were vehemently expressed through his intervention songs — which often featured poems set to music by other authors.

Cantar de Emigração, 1970

Sound installation, 2’48’’

In the early hours of 23 April 1969, a few days after the start of the Academic Crisis in Coimbra, Catalan author Ricard Salvat was taken by the PIDE (Estado Novo’s political police) to a post on the border with Spain. This event interrupted plans for the premiere of a play entitled Castelão e a sua época [Castelão and his time], which had been rehearsed for months with the students of CITAC (Círculo de Iniciação Teatral da Academia de Coimbra). In October, months after the start of the crisis, which had also spread over the summer to other events linked to academic life, some of the students involved were forcibly sent to the Colonial War in Africa. According to researcher Antonio Iglesias Mira, as a form of protest, a large demonstration was organised, and students marched from Praça da República to Coimbra-B Station, singing the version of Cantar de Emigração, featured in Salvat’s original play, which had become part of the evenings of student life. The song — initially set to music by José Niza — had as its lyrics an extract from the poem ¡Prá á Habana! by the poet Rosalía de Castro, included in her work Follas Novas, published almost a hundred years earlier in Cuba.

Reviving the phantoms of History, this biennial features a recording of this intervention song by Adriano Correia de Oliveira (from the album Cantaremos, 1970), to be played daily, near the end of many people’s working hours, in the same station where the voices of the students opposing the dictatorship once sounded. In this place of comings and goings, the verses that come to remember the transversal afflictions to migratory experiences — which mark both those who go and those who stay — resound.